From Shouts to Signals: How Ocean Chemistry Comes Alive

By GO-SHIP I09 tracer analyst Mary Kate (MK) Dinneen

“10 ON 4, 10 ON 4!”

That’s not a drill call—it’s a scientist calling out to the sample “cop,” making sure samples are collected from the right bottles on the CTD rosette (seen below), fresh from its deep dive to the ocean floor in the Indian Ocean on the GO-SHIP I09 transect. Each of the 36 bottles on the rosette holds seawater from a different depth, and every scientist has to sample all of them correctly to build a cohesive picture of what’s happening, chemically and biologically, from the surface to the deep sea.

Sometimes, the ocean tells its story even before the data hits the screen

As we move closer to the Bay of Bengal, the water feels noticeably warmer at just 50 meters below the surface—a small but telling sign. It hints at something deeper: that the ocean layers here aren’t mixing much.

An oxygen scientist adds a reagent to a fresh sample, and the water turns brown if there’s oxygen, or fades to white if there’s barely any. These simple, visual clues are the beginning of the story we’re here to tell—one about oxygen, movement, and life in the ocean’s invisible zones.

Piecing together one of many stories of the I09 GO-SHIP transect

One of the most influential water masses here and throughout our ocean systems is the Antarctic intermediate water mass. It’s a cold, oxygen-rich mass that travels all the way from the Southern Ocean, carrying oxygen and other atmospheric gases across vast distances.

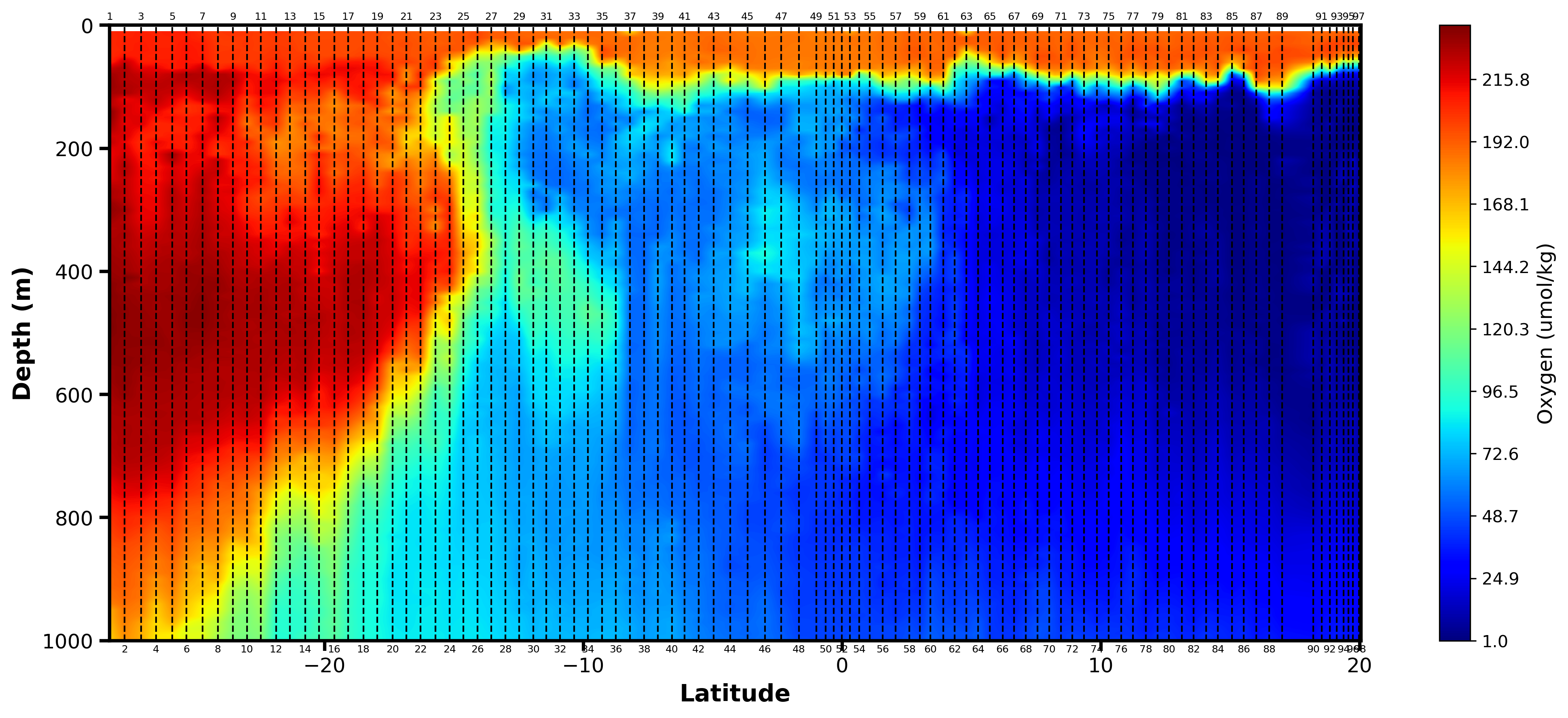

But in the northernmost part of our transect, the Bay of Bengal, scientists observe a much different chemical and physical profile…

The ocean becomes stratified—layered carefully like a yogurt parfait that prevents mixing. Freshwater from rivers and intense monsoon rains sit atop much older, saltier water. That separation creates a kind of seal, trapping intermediate water masses—like the Antarctic Intermediate water which in the Bay of Bengal has been significantly depleted of oxygen by biological processes, and diluted by the mixing of other intermediate water masses.

Because of the sharp contrast in salinity, these intermediate waters don’t mix with the surface. Instead, they form an oxygen minimum zone (OMZ)—a region so low in oxygen that only specialized microbes can survive, having evolved unique ways to grow in these harsh low-oxygen environments. Biologists from I09 will compare the microbial community distribution and genes present within these communities with chemical signatures such as low oxygen to catch a glimpse into how life adapts in extreme conditions.

Studying ocean transects like I09 over long periods—especially every ten years through programs like GO-SHIP—helps scientists understand how low-oxygen areas like this one shape the evolution of marine life and reveal patterns in water mass movement that are hard to detect at first glance. Studying them over decades, especially through global efforts like GO-SHIP, allows scientists to detect slow, powerful changes in the ocean: water masses shifting direction, low-oxygen zones creeping outward, ecosystems transforming.

Back on land…

After scientists onboard have a sneak peak of the story unraveling while at sea, all of the data is available online for other scientists and curious non-scientists alike to explore and develop their own explanations of what’s happening beneath the surface of our vast ocean systems.

Helpful definitions

CTD rosette—a sampling system involving bottles, or “niskins”, that is lowered in the ocean and collects seawater for scientists to analyze

How does it work? The CTD rosette is lowered by a strong cable and communicates data from various sensors, such as how much oxygen is present, back to scientists on the ship as it is lowered to the bottom of the sea. The scientists then decide which depths to tell the computer communicating with the CTD to sample by firing bottles at different depths as the CTD comes back up to the surface.

Example: if there is very low oxygen at a depth of 120 meters, scientists can wait till the cable brings the CTD to 120 meters and click a button on the computer that says “Fire Bottle” which within seconds closes the niskin to trap the seawater at 120 meters inside for scientists to sample when the CTD is retrieved and back on the boat.

Reagent—a chemical added to a sample to cause a chemical reaction, used in this context to determine the presence or absence of oxygen in seawater

Oxygen—a necessary chemical for microbial life; oxygen enters the ocean where the atmosphere touches the surface of the ocean and is transported through the ocean in various water masses

Water mass—water masses are physically separated in the ocean based on density which is influenced by temperature, salinity, and pressure. Example: cold water is denser than warmer water, so cold water sinks below warm water in the ocean

Intermediate water mass—these are understudied water masses that sit below surface water and above deep water

Stratified—water masses with distinct chemical properties that do not allow them to mix easily and instead lay isolated on top of one another

Monsoon—a wind system that causes a wet and a dry season in Southeast Asia

Monsoonal rains—heavy rain during the wet season of the Southeast Asia

Oxygen minimum zones—areas of the ocean with extremely low oxygen levels

About the Author— Mary Kate Dinneen is a third-year PhD student in the Moffett lab at the University of Southern California, where she studies geochemical cycling and oxidative kinetics of trace metals under extreme conditions, such as low-oxygen marine environments.