PIES in the Water

Every time I go out on a research cruise, I am fascinated by the technology that scientists use to complete their research. This cruise has been no exception. In addition to the CTD casts and Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) data being collected on this cruise, we are also recovering five Pressure Inverted Echosounders (PIES). These PIES have been down on the bottom of the ocean along the 10° W line of longitude measuring the average time it takes for sound to reach the sea surface. This dataset helps scientists better understand how waves begin and function in the ocean.

These recoveries take a lot of time and effort from everyone aboard the vessel. The scientists start this process by using a transponder and deck-box to send sound pulses to the PIES at the bottom of the ocean. The PIES respond to the frequency with their own sound signaling that they are in the region that the vessel is in. A specific sound at a specific frequency is then sent to the PIES. This is a sound that is assigned to a specific PIES which triggers the PIES to release from the mooring it was attached to and start its accent to the sea surface. This ascent takes about an hour and ten minutes, but it is different each time, so the vessel’s crew and scientists have to start looking out across the waves about an hour after the release to spot the PIES among the waves. The PIES is roughly the size of a large propane tank, so finding it out among the waves is no easy task. The recoveries at night are easier though, because of a large blinking light and reflective tape at the top of the PIES. After a joint effort by scientists and crew to spot the PIES, the crew takes over to handle the recovery.

Last night I watched as our 269-ft ship carefully maneuvered towards the small PIES, using a massive spotlight. Once the PIES was in range, the crew used a grappling hook to grab the PIES below and carefully haul it back into the ship. Watching this effort was amazing as the crew worked in sync to make this possible.

Of the five PIES we were out to recover, four of them were successful. One consistent thing about ocean technology is the inconsistency that comes with it. Large bodies of water and electronics are not meant to be compatible so having these systems out at sea always comes at a risk. For the fourth PIES recovery, the release was triggered but the PIES never rose to the surface. We sent the release twice more to ensure that it was not an error on our part, but the release mechanism was likely not working after a two-year deployment. This PIES is still out at the bottom of the ocean, and likely will be until its integrity is compromised and it floods. However, four of the five have now been recovered and will help the scientists that I am out with learn more about the ocean dynamics in this area.

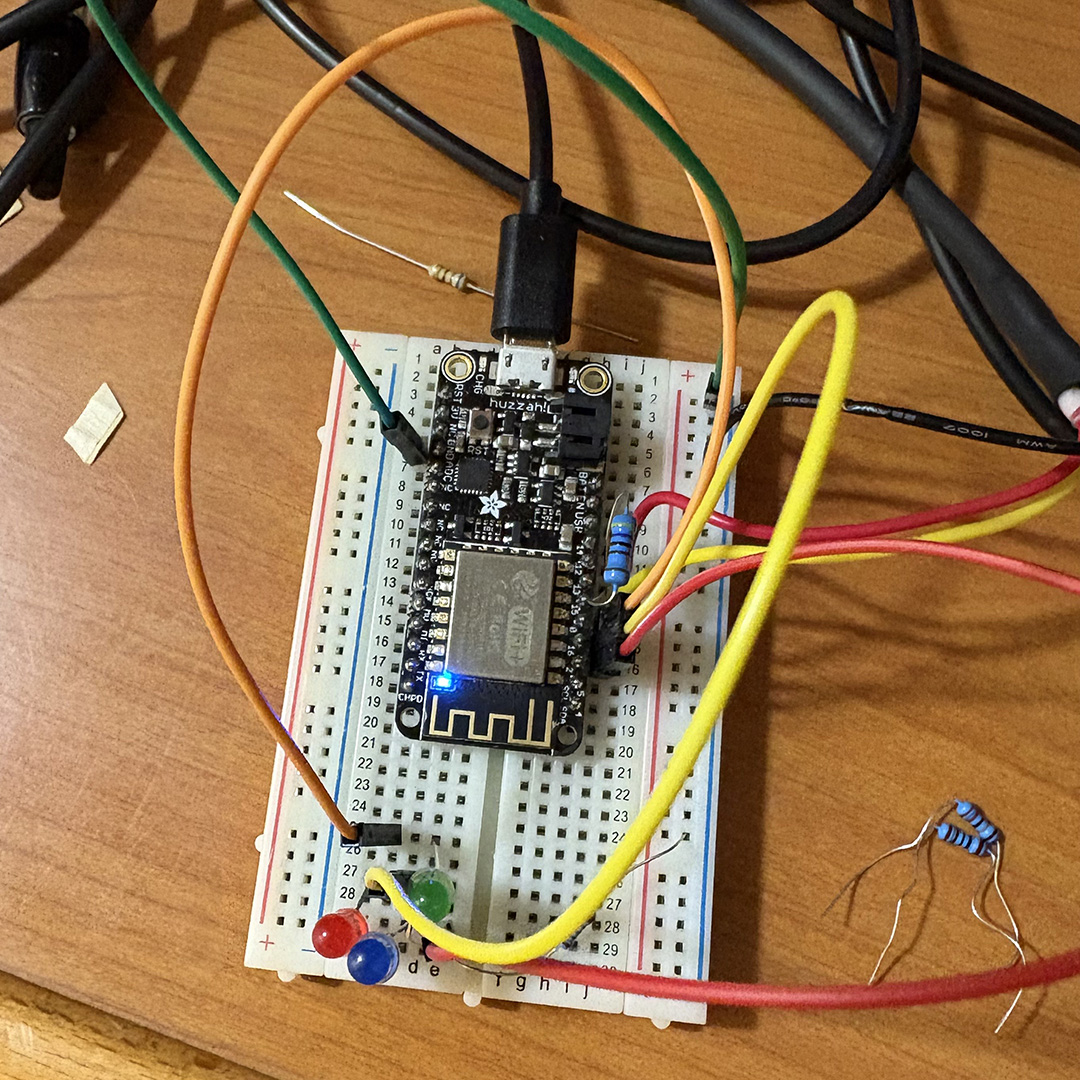

I have had a bit of break from float deployments for the time being and while I am still on watch helping with CTD casts, I have had even more spare time. I have spent my time developing new skills, working on projects, making little drawings, going to the fully stocked vessel gym, and as always, reading. I learned how to fold an origami crane with notebook paper and tried to teach myself to juggle. I have also been working with a microcontroller I brought along and working to make a temperature sensor with lights that indicate a temperature range that I can put in my bunk. I really enjoy working with electronics and microcontrollers to create circuits and small projects, so this has been a fun way to spend my time and also helps build my skills in this area.

About the Author—Paige McKay is a sophomore at University of Washington School of Oceanography and works in the UW Argo Float Lab.